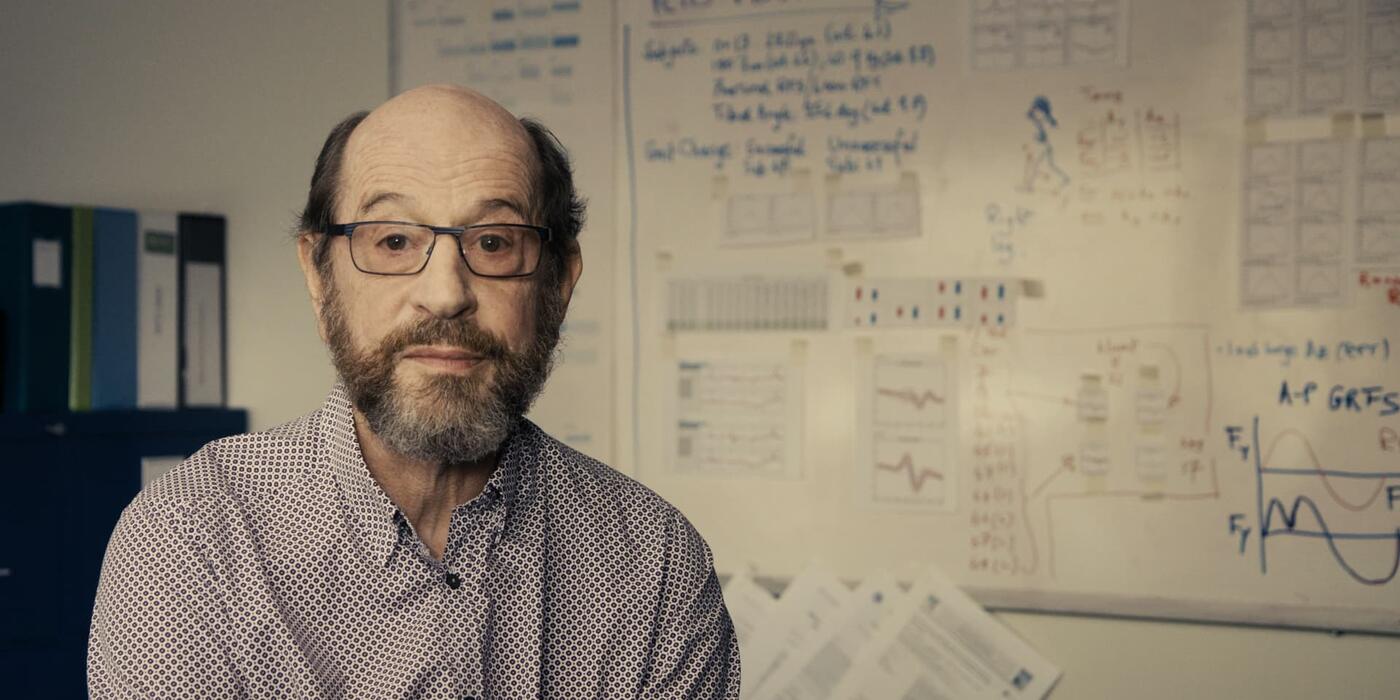

Dr. Peter Cavanagh Interview

THE GURU BEHIND THE RS COMPUTER SHOE

DR. PETER CAVANAGH

My name is Peter Cavanagh and I'm a professor in the department of orthopedics and sports medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle in the United States. I do orthopedic research, I'm interested in knees, feet ... I'm a lower extremity person. And I'm still very interested in running mechanics.

PUMA

What originally sparked your interest in your field? Tell us a little bit about that.

DR. CAVANAGH

I first started studying the human gait in 1968 for my PhD in the University of London. And I was studying muscle action and people walking, but I was always a runner myself and so it seemed to me that one could apply these techniques of gait analysis to the analysis of the biomechanics of runners. When I came to the United States in 1972 to work as a professor at the Pennsylvania State University, I very rapidly got involved in running research. And in 1975, I was invited to join a really interesting study called the Dallas Run Study, where a group of multi-disciplinary professionals got together the best athletes we could find at the Aerobics Institute in Dallas Texas. And it included Steve Prefontaine, Frank Shorter who had recently won the marathon, the Olympic marathon in 1972. And so a group of us were trying from many different aspects to find what it was that came together to produce a champion runner.

PUMA

Were you a runner then?

DR. CAVANAGH

Yes, when I came to the United States, I also started running marathons myself and that increased my interest in running mechanics and footwear for running. Back in those days, in the early 70s, footwear was extremely basic. I actually got a shoe that Bill Rogers had won the Boston Marathon in and in present day form it was so primitive you know that one would wonder that he wasn't injured more than he was. And so that really motivated me towards research that would lead to better footwear for athletics.

PUMA

As you were getting into this field of research, did computers play a role?

DR. CAVANAGH

The science in running was very basic in the early 70s. There was no monitoring of runners other than charting on paper how many miles a week they did. There were no body sensors, there were no shoe mounted sensors and although computers were common – if limited in research – they really were not popular. And the personal computer had really not made a significant impact. You know there was that famous statement from the chairman of IBM, that there's a world market for perhaps three to five computers. It’s one of the famous wrong remarks of all time.

PUMA

When was that aha moment when you decided to figure out how to put this technology into the hands of runners?

DR. CAVANAGH

In the late 70s I started doing the testing for Runner's World shoe surveys. And so, every summer about 1000 running shoes would appear in my lab at Penn State and we would use a variety of tests to rank these shoes. And it would all shake down and in the October issue of Runner's World they would say, "This is the shoe." Now that was not my view of how it should be, because I think it's more individual. But that was the start of trying to apply some science to running shoes. Now in 1980 I wrote this book called ‘The Running Shoe Book’, and this was a collection of all of the information on running shoes that I felt was available at the time. And as part of that, I did a series of interviews of whom I thought were important people in the shoe world. And one of those people was Armin Dassler.

And so, I began a dialogue with Armin Dassler and I then became the advisor for sports science to PUMA. Armin really motivated me and said, "Look, you've got all this science, and it's out there in the lab, why don't you put your thinking cap on and try and bring some of this technology to runners and let's see if we can link one of our shoes to a computer." In the early 80s we had been doing some studies in stride length in runners and it occurred to me that if you had a stride length profile of a runner than you could pretty accurately predict how far and how fast the runner was going just from knowing the time between two successive ground contacts of the foot. So, Armin got me together with a man called Heinz Gerhäuser from the University of Erlangen, which is very near to Herzogenaurach.

At the time it was a privately held company and he ran it like an empire and he said to me, "Look, do whatever you have to do, but get me this high technology shoe. And I want you to have a meeting, somewhere in the world, with all of you together." And so I talked to the Germans, and of course they wanted to do it in California. So we had a meeting on Catalina Island. Which is kind of crazy when you think about it, that we are developing a running shoe for Germany and we're meeting on Catalina Island. So we helicoptered out there and we did a little meeting. We did a lot of playing also, but we formulated the idea. It's very interesting that it was just around 37 years ago that we started talking about this. And we were very proud of our technology. We boasted for example, that the shoe was going to have a gait array with 600 transistors on a square inch.

Well it turns out that there are two billion transistors in an iPhone, in 35 years. We were using an Apple IIe computer with 48k or 68k of ram. My MacBook has got 20,000 times more storage than that. In a sense, the history of the computer shoe spans the whole history of personal computing. With Gerhäuser's electronics and my biomechanics, we put together a prototype. This is the very first prototype we made. We just put a little Plexiglas box on the back of this normal PUMA shoe. And all the electronics they were directly wired in there. There were integrated circuits, a little LED on the back and we tested this out and it seemed to work extremely well. We went forward, we got the patent attorneys involved because this was all brand-new tech nobody was doing or had done in the past. By 1985, we had a product. Looking back it was quite burdensome to the user. I wrote a manual for the shoe that was about 45 pages long. I mean a typical academic approach to a consumer product.

Back in those days, people didn't expect things to be so intuitive. Today you buy an electronics product or you download an app and the last thing you want to do is read how it works. You just want to work it. But nevertheless, here we had this elaborate 45 page manual. The software for the shoe was contained on a five and a quarter inch floppy disc. And we supplied programs for the Apple IIe, for the Commodore 64 and for the very first IBM PC that existed. Users could take the program off this disc and load it on their computer. And it was pretty full functioned. When you go for a run, you would come back and you would plug the shoe into your computer. It would download the information, compare it with your calibration data, and log it in to your personal tracking history. It allowed you to see how much distance you'd done in a week, a month, a year. It calculated the caloric cost of your running. And so by 1985 we were ready to launch this on the market.

Our official launch was done at the University Club in New York City. We had a press conference, we had a runner on the treadmill, we showed how the shoe worked. You know you always hold your breath at this time, that everything was going to work. And it did, everything worked fine. The reaction to the shoe was a sort of genuine incredulity. Like, why would you want to do this? Why on earth would you want something that tells you how far you've run, how fast you've run, how long you've been exercising ... why would you want to do this?

In answer to that, is to ask: what if you, at the beginning of the 20th Century, had bought a car and it would have neither a speedometer or odometer on it. People then asked, why would you need to know how far you're driving? And why would you need to know how fast you're driving? With the RS Computer Shoe, I predicted that by the middle of the 90s, that nobody would be buying a running shoe or go for a run without wanting to know how far, how fast, how many calories. It turns out I was wrong. It didn't happen until the middle of the first decade of the 21st Century. But it really did happen. All of these people who said why would you need to do this are now facing millions of people who are obsessed with how far, how fast, how many calories. At the time it was a technology that nobody thought they needed.

PUMA

What was it like as a researcher, to be challenged by a commercial pursuit? When you were given all the tools and resources you needed to build the RS Computer Shoe, what was that like?

DR. CAVANAGH

When Armin Dassler said to me, "I want you to build this, to build something really special." he wanted something special that would identify PUMA as technologically advanced and capable of building things into a shoe that had never been done before. I was of course delighted, because here was somebody in the commercial sector saying, "Okay, take this stuff that you learned about running mechanics and turn it into a product." The opportunity to have fairly limitless resources, to go ahead and produce a product to me was just like being let into the toy shop and given the key.

PUMA

As you reflect back has the experience of the RS Computer Shoe and the partnership that emerged from it informed your research or propelled you as an individual?

DR. CAVANAGH

For me it was my first inkling that some form of body-mounted sensors was the future for tracking people's activities and running mechanics. My work and the work of all my contemporaries was absolutely based in the lab and so when I look back today with 35 years of hindsight, and I see what I'm interested in doing today, it was really directly informed by that first body-mounted sensor – shoe-mounted, but it was body-mounted because the shoe was on the body.

Today, when I put a small accelerometer on somebody or I put a knee sensor on a patient who is recovering from a knee replacement, and I can monitor them all day and get information on what they're doing and how their rehabilitation is going, I see that as being directly informed from these initial experiments with the RS Computer Shoe. The work I've done in space for example, I've done a number of experiments on the space station, where I have tracked astronauts for the whole day, for many days at a time, to see their activity profile. That's part of this same thread, which all begun with the RS Computer Shoe in 1985.

PUMA

That's incredible, how does that make you feel?

DR. CAVANAGH

I'm pleased to see that body-mounted sensors have become important. I'm pleased to see that runners now are exploiting technology to the maximum. I am crazy about gadgets myself and try to get the very latest gadgets that I can. I'm a little regretful that the technology wasn't better accepted at the time and I think we could have short-circuited the activity tracking developments by perhaps 15 to 20 years, if there had been a bit more open-minded approach on behalf of the market. It was just not accepted. People did not think it was needed. And it was at the time of the explosion of personal running, everyone was beginning to run marathons, people were running for fitness and there was a real explosion in running as a fitness activity. And so, it is surprising that it wasn't something that caught fire and that it actually laid dormant for about 15 to 20 years until activity trackers became a big thing in the marketplace.

PUMA

Was the RS Computer Shoe the first attempt you made to merge computer tracking with running?

DR. CAVANAGH

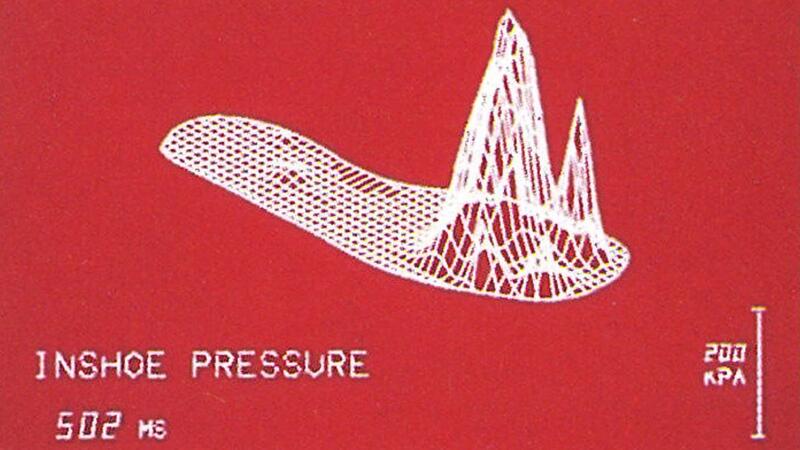

What was new about the RS computer shoe was that it was not a step counter, and that's rather ironic because many of today's activity trackers are just step counters. I believe that step counting is not enough. What we realized is that as you run faster, the time between your footfalls gets less. So, we were able to get a graph that showed that as you run faster, your time between contacts goes down. And that was the key for us, to be able to go beyond the pedometers which had been in existence for many, many years. But if you want to personalize the data, you've got to build the runner's own profile into the shoe. We could achieve accuracy that was greater than the pedometers of the past and is greater than today's non-GPS trackers. Because you have to know something about the individual. Counting steps, it's motivational, but it's not accurate for running distance, running speed, and caloric cost.

The breakthrough we had with this shoe was to say pedometers won't work, step counters are not enough, and with the computer what we can do is we can build the person's profile and then using regression methods we can find where we are on a given day. What the speed, the distance, and the caloric cost was.

PUMA

What did the RS Computer Shoe do? What were some of the specs?

DR. CAVANAGH

I have to admit that I was a bit surprised going back through the manual after all these years to find out just how fully featured this product was. I don't know if people used all the features, but you could for example, program a distance into the shoe and you could get the shoe to beep at you when you finished your given distance. That was one of the features. But the normal operation would be the following: You'd be out ready to start your run, and you'd lean down and press a button on the shoe. And that would start everything. From that point onwards, the shoe would measure the timing of every footfall of the right foot. It would measure the timing of steps on the right side. And it would store those in its – what at the time we thought was a massive memory, but it turns out to be a tiny little amount of memory – it would store those for as long as you ran.

You'd come back home or to your running club and you'd plug the shoe into your Apple IIe computer or your Commodore 64, and through the printer port you would download the information and you'd put it into the program. I wrote the software in what was called Applesoft, which was Apple BASIC which used to run on the Apple IIe. Then the information that was read from the shoe would be analyzed. It would calculate how far you'd run, how fast you ran, how many calories you ran, and it would write them to the floppy disc and you could then recall and plot your journal. You could use it either for record keeping or motivation. And many people with computer shoes could use the same computer. Because computers were not very wide spread at the time. It was pretty interesting because one of the remarks about the $200 price tag was that, "Well if you're concerned about the $200 price tag, well don't worry, because you'll find that the computer is five to ten times more expensive than that." You know at the time, that's what you'd pay for an Apple IIe. You'd pay a thousand bucks.

PUMA

What is it like seeing the original shoe that we have here?

DR. CAVANAGH

At the time, I thought it was a pretty good-looking shoe, that was not a widely-shared opinion. A lot of people said it was ugly. And I find that there are certain shapes which don't age. The Concorde is a timeless shape. The Seattle Space Needle's a timeless shape. And I actually don't think this shoe looks too darn bad right now. It's definitely retro but you know retro's kind of fashionable too. When I look at the shoe a couple of things go through my mind. First of all the material that was used for the mid sole was at the time an advanced polyurethane. And it has oxidized with time and so it makes me sad that the shoe that's in the shoe museum in Toronto is kind of disintegrated in the mid sole. And so I'm hoping they're going to get one of the new shoes and say this is a replica. But it brings back a lot of good memories for me. This was a very, very fun development project.

At the time, I was commuting to Germany every couple of weeks from Pennsylvania. And you know when you're in your 30s that's no problem. And I would ride from an overnight flight in Frankfurt, drive to PUMA and start the day's work. It takes me back to those days, and it's great to see the shoe, because I do think that the literature on the patent documentation shows that this was the seed from which activity trackers have grown. And they have grown in many different ways and they really help and motivate people in their exercise. I'm very pleased about that.

PUMA

When PUMA called you and said, "Hey, you know we're thinking of remaking the shoe," what did you think?

DR. CAVANAGH

When PUMA called and said that they were going to remake the shoe it was a huge surprise to me. Obviously, I knew that this was not something that was going to be a high-volume market product. I'm now at the point towards the end of my career, where I'm going to be retiring very soon. So for me, it was just a very nice little postscript to some of the work that I have done ... that it's being recognized after these many years of being somewhat of a sort of a formative development in activity tracking.

PUMA

And as you move into present where do you see technology going with this? How is it informing companies or the medical field? What are some things that are of interest to you?

DR. CAVANAGH

Where I see tracking going in the medical field, which is what I've been involved with for the last 20 years, is I think we're going to be embedding trackers in orthopedic devices that we put into people. There are many patents already for implanted sensors in joint replacements for example. At the moment I'm using externally mounted sensors, but as soon as the power and battery issues can be solved to make them both with enough capacity and with enough safety, I think we're going to see it pretty routine, that anybody with an orthopedic device is going to have tracking as part of it. I think the only limits for footwear and athletic clothing in general are really going to be on privacy and how much invasion of privacy are people going to accept. Are we prepared to buy clothes with trackers in them that will be helpful to us but also potentially invasive? We are at this moment I think, where in the United States, we've kind of given up on privacy and we don't care.

People in Europe are much more circumspect about divulging aspects of their personal and private lives which is implicit when you're wearing 24 hour activity tracking. But in the concept of disease and arthritis, and rehabilitation from surgery, to be able to quantitatively monitor many aspects of rehabilitation is there. It's stunning to me that we don't do this. The battle I had in 1985 trying to tell the running community that they need activity tracking, I'm fighting again with the orthopedic community in 2017. I have developed activity tracking for patients who have had knee joint replacement. And people are say, "Why would you want to know that?" And I'm thinking to myself, "Where have I heard this before?" I can only make yet another prediction, like my wrong prediction that everyone would be tracking activities in the mid 90s. I think in the 2020s, many orthopedic patients will be being tracked, so that their rehabilitation can be guided and they can make more progress. There is a rather discomforting circularity to the conversation I'm having now, to the conversation that I had with the running community in the 1980s.

PUMA

As you close out your career, is there anything that really excites you about where technology is going or the part you played in it?

DR. CAVANAGH

What's exciting for me now as I leave this field of biomechanics behind is that I see a group of young scientists who have grown up to be so completely fluent with technology that they are going to make the kind of developments that we could not have dreamed of. I learned computer programming when I was 21, and I started coding in FORTRAN and BASIC when I was 21 and when I now see my 11 year old grandson whose already coding games, and I am just stunned as to how much potential we left on the table that will not be left on the table by the next generation.